The Great Interconnector Swindle

Our electricity interconnectors are costing us a fortune to cover up shortfalls in our dispatchable generation

Introduction

In 2020, the National Grid said (my emphasis):

“Interconnectors are in many ways the perfect technology to integrate renewable energy and ensure reliable, affordable and decarbonised energy for homes and businesses…

“By linking Britain to neighbouring countries, interconnectors can import cheaper clean energy when it’s needed, while exporting excess power – so that both Britain and its neighbours have access to a broader and more flexible supply of electricity.”

Just before the end of 2023, Energy Secretary Claire Coutinho was lauding on X the new £1.7bn, 475 mile Viking interconnector to Denmark. She was also quoted on the National Grid Press release as saying:

“The 475-mile cable is the longest land and subsea electricity cable in the world and will provide cleaner, cheaper more secure energy to power up to 2.5 million homes in the UK.

“It will help British families save £500 million on their bills over the next decade, while cutting emissions.”

This inspired me to take a deep dive into the interconnector data, to see if the claims of cheaper power are true.

The main sources for this analysis are:

National Grid interconnector data which shows the cleared volume and the Volume weighted price for each auction.

Daily reference prices from the Low Carbon Contracts Company (LCCC).

Volume and Value of Electricity Traded Over UK Interconnectors

Figure 1 shows the volume of electricity traded over the interconnectors by quarter for the years 2021-2023. The data begins part way through December 2020, so is excluded from the analysis.

In 2021, we sold far more electricity (2,756GWh) than we bought (396GWh) over the interconnectors. In 2022, the position reversed, and we bought (3,168GW), far more than we sold (805GWh). In 2023 the situation was more balanced, but we still sold more than twice as much (2,152GWh) than we bought (1,097GWh). It appears that the third quarter of each year always sees the most total trade.

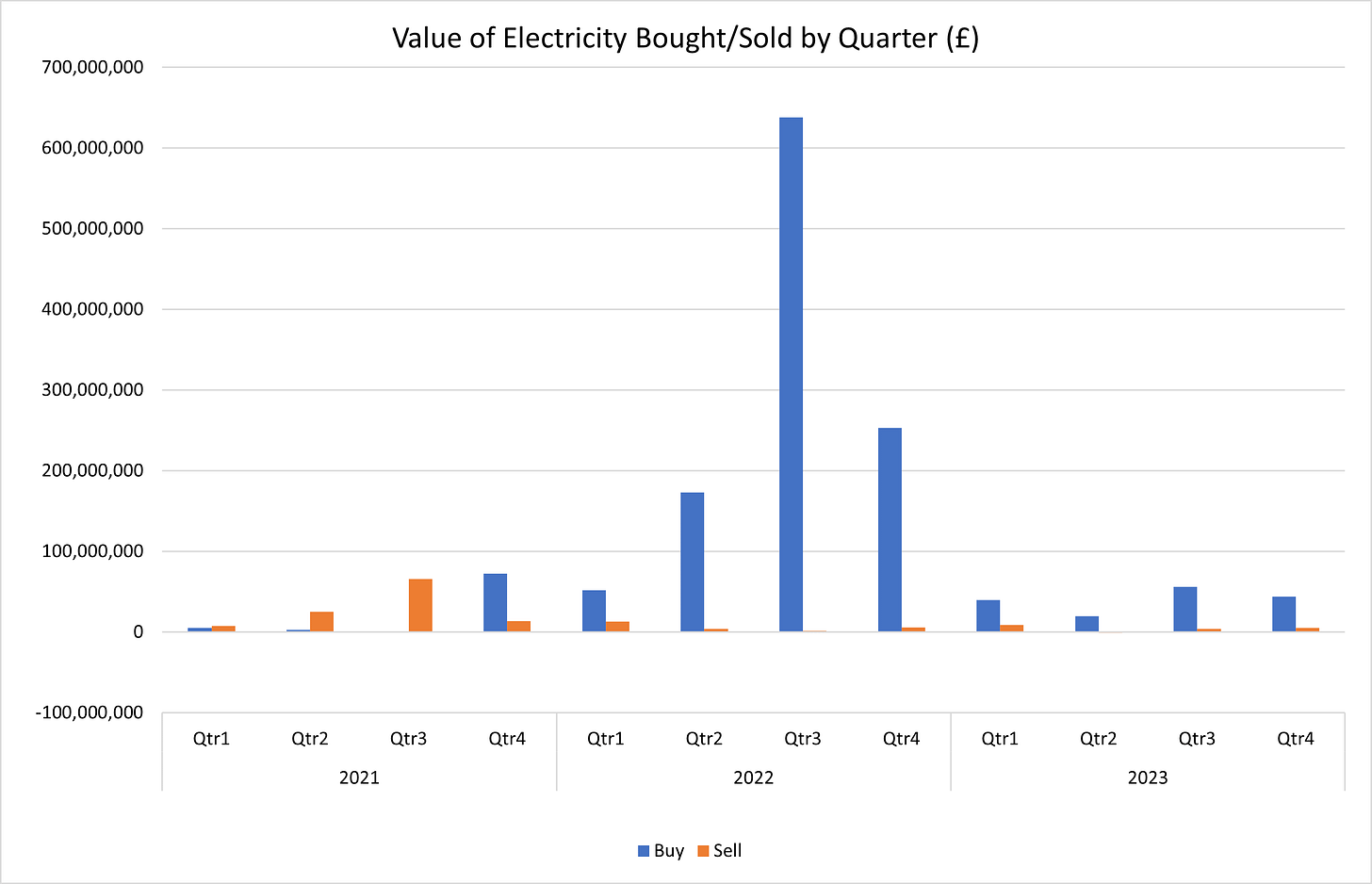

Figure 2 shows the value of electricity traded in the same periods. The total value of the trades is calculated by multiplying the volume of traded in each auction by the volume weighted price. As we shall see below, sometimes we pay people on the Continent to take power away and the price is negative for some sales transactions. When the data is aggregated, this has the impact of reducing the apparent sales value.

In 2021, even though we sold far more electricity than we bought, the value of the trade was more even with £112m of sales and £82m of purchases. 2022 was an exceptional year with £1,116m of purchases and only £25.2m of sales. In 2023, there was a much higher value of purchases (£160m) than sales (£16.7m) even though the volume sold was double the volume we bought.

Electricity Interconnector Transaction Prices Compared to Daily Market Prices

Figure 3 compares the average price of purchases and sales through the interconnectors to the market price of electricity on the day of the transaction. The Low Carbon Capture Company publish a dataset that shows the subsidies paid to various renewables through CfD contracts each day. That dataset also includes the Market Reference Price for wind and solar on each day. I have used this as my market price for each day. Typically, this reference price is set by gas-fired electricity.

The dark blue bars show the average buy-price in the quarter. The light blue bars show the average of the market prices on the day of the transactions. The dark orange bars show the average sell-price in the quarter and the light orange bars the average of the market prices on the day of the transactions.

We typically pay more than the market price for buys and accept less than market price for sells. Looking at the detailed data, the maximum purchase price was £6,599.98/MWh on 20th July 2022 when the reference price was £247.91/MWh. The minimum sale price was £‑404.71/MWh on 29th May 2023 when the reference price was £63/MWh. It is also interesting to note that for the whole of 2Q23, the average sale price was slightly negative (£-0.22/MWh). These negative sales prices mean we paid others to take this electricity off our hands.

Figure 4 zooms in on December 2023 and shows the buy-prices and sell-prices compared to the market reference price for each day.

Again, we can see the blue buy-prices are generally above the market reference price and the orange sell prices are generally below the reference price. In fact, for part of 1st December, we had to pay over £700/MWh for interconnector supplies when wind generation was low and demand was high. We also paid over £400/MWh on 6th December even though wind was generating over 6GW. Whereas, over the Christmas period we were paying people to take surplus generation off our hands. This might explain why Greg Jackson, founder of Octopus Energy was boasting about paying his customers (see Figure 5) to use more electricity in the early hours of Christmas Eve, you know the perfect time to put on an extra load of washing.

Do not worry about Greg, the wind generation companies in his supply chain will have still been paid substantial sums in subsidies to produce power that has negative value. Subsidies that we pay for in our energy bills.

Frequency Distribution of Electricity Interconnector Buys and Sells

To further illustrate the point, Figure 6a shows a frequency distribution of prices for interconnector buy and sell transactions from 2021 to 2023.

As you can see, we have perfected the art of buying high and selling low. A sizeable proportion of the sales transactions have a negative sales price. The peak is in the £40-60/MWh range. Most of the interconnector buy transaction prices are above most of the sales prices, with a very wide spread that peaks around £180-200/MWh. However, there is a cluster of buys in the £0-20/MWh range and a sizeable number of buy transactions over £600/MWh.

Figure 6b shows the same data, but just for 2023.

Again, for a sizeable number of transactions, we were paying others to take our surplus electricity and the peak of sales transactions is in the £40-60/MWh range. There is little overlap between sell and buy transactions, with the peak buys in the £100-120/MWh range, again with a long tail and quite a few deals over £600/MWh.

Interconnector Buys and Sells by Time of Day

It is also instructive to look at the volume of electricity traded by time of day. Figure 7a shows the volume traded in 2023 by time of day.

As we can see, most of the electricity sold is from 22:00-06:00. There is also a residual tail of sales from 07:00-14:00, reflecting the demand lull in the middle of the day. Most is bought in the morning peak from 05:00-07:00 and then again during the evening peak from 16:00-21:00.

As might be expected we are selling most when demand is low and buying when demand is high, reflecting the fact that we are not really in control of generation and cannot use it to match demand.

This is further illustrated by Figure 7b that shows the value of electricity traded by time of day.

Even though the volumes sold during sleeping hours are high, the value of that electricity is low. In aggregate, the electricity sold during the middle of the day has negative value, so we pay others to take it off our hands. By contrast, we pay through the nose for the electricity we buy at peak hours.

Losses on Interconnector Buys and Sells

Figure 8 quantifies the “losses” from buying during peak hours and selling at negative prices during the lull in the middle of the day. For buys, the purchase price minus the market reference price for that day is defined as a loss. For sells, the market reference price minus the sale price is defined as the loss. Of course, sometimes we buy lower than the reference price and sell for more than the reference price and make a notional profit. All the transactions are aggregated together to calculate the net loss.

Overall, in the period 2021-2023 we “lost” £811m on the interconnector transactions, with £445m of the total loss being on the buys and £366m on the sales. If we treat 2022 as an outlier year, it looks like the trend is getting slightly worse over time, because the losses on sales in 2023 are higher than in 2021 even though the volume sold was much lower.

Conclusions

Coutinho’s claim was interconnectors “provide cleaner, cheaper more secure energy.” Let us go through her claims one by one.

We do not tag each electron in the network to identify whether it was produced from a wind farm or a coal-fired power plant. So, we cannot say for certain one way or another whether the power provided is clean or not. However, when import prices are significantly above market rates, we can be fairly certain that generation from wind and solar across Europe is low and that every sinew is being stretched to bring online every single dispatchable power source to meet demand. These marginal dispatchable sources are likely to be diesel engines and coal-fired power stations. Conversely, when we are selling electricity at negative prices, we can be reasonably sure there is excess wind and solar supply. This means that our imports from the interconnectors are more likely to be marginal “dirty” sources and our exports more likely to be “clean.” Probably the opposite of what the Energy Secretary claimed.

It is crystal clear that interconnectors do not provide cheaper energy. In fact, quite the opposite is true. The data shows that interconnectors have helped us to perfect the art of buying high and selling low. The price we pay for imports is consistently above the market price and the price we get for exports is significantly below market rates and we frequently pay others to take surplus power off our hands. In what world does it make economic sense for consumers to pay elevated subsidies to generate wind and solar power, and then pay people overseas to take the same power off our hands?

The security point is more nuanced. In a narrow sense, the interconnectors do provide some security because even though at times we pay excessive prices for electricity, the interconnectors have allowed us to keep the lights on. However, we are in this position because people like Alok Sharma gleefully blew up coal-fired power stations, so destroying our domestic dispatchable capacity. This has meant we are now dependent upon the kindness of strangers in Europe to keep the lights on. As other European countries continue down the path to net-zero, destroying dispatchable sources (like Germany’s nuclear power plants), and installing more intermittent sources of energy, we may not be able to rely upon this kindness. It is likely that Europe-wide electricity surpluses and deficits will synchronise, meaning that there will be more times when we pay others to take our surplus power and more times we pay extremely high prices when demand is high and renewables generation is low. Overall, this is not a position of security, it is a position of weakness and insecurity.

Moreover, it is also clear from the data that we are a price-taker, not a price-maker in the market. This is because we do not have sufficient dispatchable capacity to meet demand. Again, this is a position of weakness, not strength.

Evidently, there is a massive disconnect between the rhetoric about interconnectors and the reality. The claims about clean, cheap and secure energy are bogus. Sadly, it is becoming clear that in many cases, when it comes to pronouncements involving Net Zero, the opposite of what the Government tells us is true. The interconnectors are a giant swindle. They are nothing but an expensive sticking plaster over the reckless mismanagement of our dispatchable generation capacity. This can only be solved by investing in new sources of dispatchable supply (like gas and nuclear) so we can regain a position of strength. This investment would increase energy security, make us a price-maker in Europe and turn the interconnectors from an expensive liability into a valuable asset.

Acknowledgement: Thanks to Steve Loftus for his Twitter/X thread that provided some inspiration for this article.

A version of this article has also appeared in the Daily Sceptic.

If you enjoyed this article, please share it with your family, friends and colleagues and sign up to receive more content.

Another depressing essay on the economic and scientific madness and ineptitude of our politicians. The public would be aghast if they knew but the relentless propaganda makes it very difficult for reason and reality to prevail (or even get a voice). My Iron Law of Govt strikes again.... Everything they do is net negative for Society at large. Their interjections into the market always deliver diametrically opposite outcomes from those they claim to want. Always.

You ask "In what world does it make economic sense for consumers to pay elevated subsidies to generate wind and solar power, and then pay people overseas to take the same power off our hands?" Answer - in the world of eco-zealots and grifters and incompetent politicians.

When the energy system collapses (as it surely will) not one of these politicians, NGOs, or corporations will apologise. Not one. If you don't believe me just look at the Post Office scandal unfolding right now.

Thanks David. Another detailed, mind-blowing expose of yet another aspect of the Net Zero scam, highlighting the progressive destruction of our previously robust, secure and remarkably efficient energy infrastructure via the treasonous and insane actions of our politicians. I hope Toby Young picks up on this article and publishes it in the Daily Sceptic to ensure wider coverage, but it really deserves to be in the main stream media via the Telegraph and Daily Mail. It is vital that the general public are made fully aware of this scam.