Re-exposing the Hidden Costs of Renewables and Net Zero

How electricity prices have risen despite increasing generation from "cheap" renewables

Introduction

First of all, thank you to all my subscribers. Last week was the first anniversary of starting this Substack. My very first article was published on January 17th 2023. It exposed the hidden costs of renewables and net zero. I thought it would be interesting to mark the first anniversary and revisit the figures twelve months on.

The purpose of the first article was to answer the question, if we’re following Net Zero and generating more power from “cheap” renewables, why did electricity costs rise sharply before the war in Ukraine? This article will update the figures and look at where we are now.

It is often claimed that renewables are the cheapest form of electricity generation, for example by the World Economic Forum. In addition, others like the Natural History Museum (yes, that well known economic think tank) have claimed that net zero “is cheaper and greener than fossil fuels”. These thoughts are propagated by the Government (DESNZ) in reports such as their electricity generation cost reports from 2023, 2020 and 2016. If the claims of cheap renewables were true, then surely generating a higher proportion of our electricity from the lowest cost sources should bring overall prices down.

We get the first indication of the true position by comparing the 2023 Generation Cost report to reality. That report made a spectacular error (or told a big lie) by claiming that offshore wind could be delivered in 2025 at £44/MWh (in 2021 prices). This claim was comprehensively demolished when nobody bid to build offshore wind in 2023’s Allocation Round 5 (AR5). They have now shown a bit more realism by releasing revised expectations for AR6 as shown in Figure 1.

Clearly, the starting claim of cheap renewables is not true, and they are getting more expensive. But as we shall see the generation cost is not the whole story.

Industrial Energy Price Trends and International Comparisons

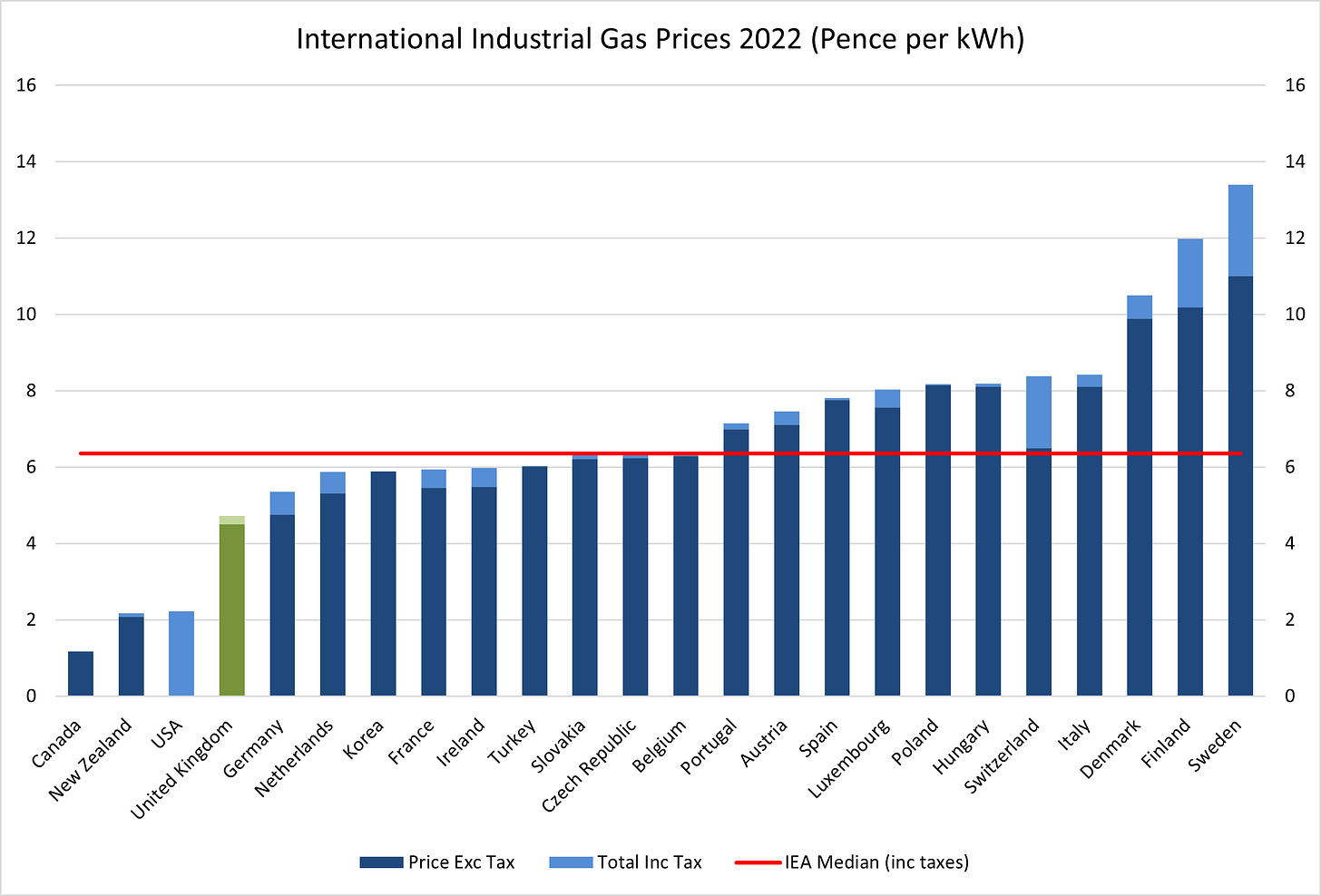

Last year’s article started with a comparison of international industrial energy prices. DENZ publish historical data comparing UK industrial gas and electricity prices over time (Tables 5.7.1 and 5.3.1 respectively). Each download has a chart showing how UK prices compare internationally. There’s now a new version of the data.

Figure 2 shows a comparison of industrial gas prices for 2022. The UK improved its ranking from 8th cheapest to 4th cheapest after the USA, New Zealand and Canada.

The other countries in the comparison are European and as might be expected their prices rose more than in the UK, so they fell down the rankings. Even though the UK ranking improved, prices are still more than double the best countries and they went up nearly 70% from 2.78p/kWh to 4.72p/kWh.

In 2021, the UK had the highest industrial electricity prices. However, as Figure 3 shows, the UK improved its position somewhat to fifth worst in the table for 2022, although the worst country, Italy, did not appear in the chart for 2021.

UK prices rose from 13.66p/kWh in 2021 to 18.55p in 2022, more than double the prices in the USA, Canada and Korea. Notably, prices in Germany are almost as high, despite their massive investment in wind and solar projects.

As can be seen in Figure 4, from 2008 to 2020, industrial electricity prices rose 53.8% while industrial gas prices actually fell slightly over the same time period.

Both gas prices and electricity rose in 2021 and 2022 as gas prices started to spike as demand increased after Covid lockdowns ended and supply could not keep up with the extra demand. Of course, there was an additional increase in 2022 as the sanctions on Russian gas tightened European supply even further.

Changes in Electricity Mix

The first article also looked at changes in electricity mix over time and of course, and updated data is now available (Energy Trends Table 5c). Figure 5 shows how UK Electricity supply and net imports have changed since 2008. Overall, there’s a 21% reduction in supply. Within that, the mix has changed dramatically. Renewables, meaning hydro, biomass, wind and solar have increased by nearly 550%. Strangely, after rising steadily for years, net imports turned negative in 2022, although this data is at odds with National Grid’s data on interconnectors. Zero-carbon nuclear has declined nearly 9%. Coal generation has declined more than 95%, oil by 70% and gas by 30%.

A slightly different story emerges looking at the change in share of generation for each source. Figure 6 shows how the share of generation has changed between 2008 and 2022. First point to note is that coal has fallen from a 31.2% share to 1.7%. The share of gas has fallen too from 45.7% to 40.3%.

Overall, fossil fuels have fallen from over 78% to just under a 43% share. The share of renewables has risen from 5.2% to over 42%. Most of this is driven by a massive increase in wind and biomass generation. Nuclear has risen from a 12.6% share to 14.5% despite overall nuclear generation falling.

How can it be that “cheap” renewables have risen as a share of generation so substantially and we have seen a massive increase in electricity prices even though gas prices were relatively stable up to 2021?

Hidden Costs of Renewables

The answer is in the hidden costs of renewables. First, wind and solar are intermittent sources of energy: no electricity is produced if the wind doesn’t blow (or blows too hard), or the sun doesn’t shine. They need to be backed up by reliable sources of generation and it costs a lot to keep these units on standby and even more to bring them online. In addition, most “cheap” renewables require subsidies to make them economically viable. Overall, there are three elements to the hidden costs:

· Levies, documented by the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR)

· Feed in Tariffs (FiT), documented by Ofgem

· Grid Balancing costs arising from increased intermittent sources, documented by the National Grid ESO

There is also a fourth hidden cost, which is the cost of the interconnectors we now need to maintain a stable supply. Typically, we sell through the interconnectors at a low (or even negative) prices and buy at high prices as covered in this article.

Levies are made up of several components documented in the OBR’s Economic and fiscal outlook – supplementary fiscal tables: receipts and other publications. Overall levies fell by £0.16bn in FY2022/23 to £7.32bn compared to the prior year. Renewables Obligations (ROCS) increased by £0.46bn. This was offset by a change in Contracts for Difference (CfDs) of £0.42bn from a cost of £0.29bn to a contribution of £0.13bn and a reduction in capacity market costs from £0.9bn to £0.7bn.

Feed in tariffs (FiT) are paid to small renewable energy producers. Ofgem produces an annual report showing the cost of these FiT payments. These costs vary by the amount of energy generated and the unit payment. The unit payments are index-linked, so the unit costs will rise with high inflation. In year ended March 2022, the cost was over £1.5bn and rose to over £1.7bn in FY22/23.

Grid Balancing costs are documented by National Grid ESO in their Monthly Balance Service Summaries (MBSS). These reports show the amount spent each month to keep demand and supply in balance at all times. The total cost in the year to March 2023 was £4.1bn, up from £3.1bn in the prior year. It is looking like the costs to March 2024 will fall with gas prices as the cost of replacement gas-fired electricity has fallen.

Figure 7 shows the combination of the data from all three sources since 2010. The CRC Warm Home discount has been stripped out from Levies and the Capital Markets cost indicated has been added to the cost in each report. The National Grid ESO data before 2013-14 is no longer available on their website. However, the NAO helpfully produced a report in 2014 containing the data from earlier years in their Figure 9. Using their chart, I have estimated the MBSS costs for the earlier years to +/-£20m.

The total costs have risen sharply from £1.5bn in 2012 to £13.2bn in 2021. They fell back a bit in 2022 to £12.2bn but began rising again in the year to end March 2023 to a value slightly below 2021’s level.

The cost of levies has soared over the years from £0.5bn in 2010 to £9.7bn in 2020. Levies stabilised in 2021, then fell back in 2022 and 2023 as CfD costs fell. However, total costs are rising again with increasing balancing costs. The OBR expects total levies to rise to £9.6bn in FY2023/24 and to continue rising to £13.1bn in FY2026/27 before falling in subsequent years. It should be expected that FiT costs will rise in line with inflation. It is not clear what will happen to grid balancing costs after falling in FY2023/24. However, I suspect total costs will rise again in the year to FY2023/24.

Impact of Hidden Costs of Renewables

It is now possible to pull all this together and update the impact of these hidden costs on electricity prices.

First, look at the correlation between the rising hidden costs of renewables, the increasing price of electricity and the growth in share of renewables. Figure 8 shows how the increasing hidden costs of renewables have changed with the increasing market share of renewables.

As we can see, the total of levies, FiT and balancing costs rose up to 2021 and likely drove the increase in electricity prices. Gas then became the driver of higher electricity prices in 2022 as the hidden costs fell slightly. As we saw above, the hidden costs rose again in 2023. Although the official data from the Government is not in yet, both gas and electricity prices have fallen too. I suspect that 2022 is a blip in the data and in 2023 and subsequent years, we will see hidden costs rising again.

We can also calculate the hidden cost of renewables per MWh generated by dividing the total of levies, FiT and grid balancing costs by the total renewable supply. The result is shown in Figure 9.

Even though the costs per MWh dipped in 2022, there is an obvious upward trend that belies the claims that renewables are getting cheaper. In fact, looking at the CfD payments for wind in 2023 from the Low Carbon Contract Company, we can see that CfD costs have risen markedly with record subsidies in December 2023 (see Figure 10).

The true costs are even higher because the ROC generators also get paid for the electricity they produce. In addition, the not inconsiderable costs of connecting these new wind and solar farms to the grid have not been included in this analysis.

This analysis has also spread the hidden costs evenly between wind, solar, biomass and hydro generation. Although there are big environmental problems with biomass (burning trees), generally it is producing baseload power so the grid balancing costs shouldn’t really be attributed to it. The £3.1bn in grid balancing costs should really be attributed just to wind and solar, further increasing their hidden costs per unit.

Conclusions

Although the Government, investment banks and net zero advocates claim renewables are cheap, they are wrong. Even though their costs fell relative to gas in 2022, the CfD strike prices are index-linked and only rise over time. By contrast, gas prices have fallen recently so the alleged advantage of renewables has evaporated.

Time to face the facts and acknowledge that renewables are very expensive and will continue to be so.

If you have enjoyed this article, please share it with your family, friends and colleagues and sign up to receive more content.

I pointed out on your interconnector analysis article that the NGESO data you used only applies to the balancing trades that NGESO themselves conduct. I did a fuller analysis of each interconnector using the data from BMReports/Elexon and IMRP day ahead hourly prices (which are a bit more favourable than NGESO's balancing trades, although those will be included in the overall volume of flows). Summary:

Our trade last year with France included some 160GWh of counterflow on Eleclink and IFA1, with one exporting while the other imported, sending electricity round in circles, and adding 160GWh to exports and imports. These events were frequent – almost daily, and often lasted up to several hours. The worst case saw the entire 1GW capacity of Eleclink being used in counterflow, though usually such flows were 500MW or less.

Trade with France valued at hourly day ahead prices was

GWh Eleclink IFA1 IFA2 France

Import 4,648 7,159 3,803 15,610

Export -813 -1,265 -675 -2,753

Net Import 3,835 5,894 3,128 12,857

Import £95.07 £96.78 £98.37 £96.66

Export £93.53 £83.98 £87.46 £87.65

Utilisation 62.3% 48.1% 51.1% 52.4%

The other Continental links:

GWh BritNed NEMO NSL Viking

Import 4,262 3,983 8,942 64

Export -1,587 -1,003 -414 -12

Net Import 2,675 2,981 8,529 52

Import £104.09 £99.15 £99.27 £68.07

Export £79.19 £79.63 £37.33 £70.45

Utilisation 66.8% 56.9% 76.3% 0.6%

Ireland

GWh E-W Moyle Ireland

Import 239 422 661

Export -1,915 -2,454 -4,369

Net Import -1,676 -2,032 -3,708

Import £107.72 £103.45 £105.00

Export £86.80 £91.21 £89.28

Utilisation 49.2% 65.7% 57.4%

Overall

GWh Total GB

Import 33,522

Export -10,137

Net Import 23,385 =4,984MW on average

Import £98.70

Export £84.16

Utilisation 59.3%

As you said

In addition, the not inconsiderable costs of connecting these new wind and solar farms to the grid have not been included in this analysis.

The costs of connecting all these renewables has been estimated as having to add 5 TIMES the grid cabling at a cost of 54bn which is all going to be added to bills and is directly attributable to Renewables, and of course 5 times the cabling comes with 5 times the maintenance costs which will also be going on your bills.

AND we haven't even started to cross the Rubicon of trying to build the infrastructure and back up kit necessary to remove gas from the grid, and that's a whole new world of costs and pain for bill payers which will costs multiples of the cost of sticking with gas.

How long before the public start to ask the question - if renewables is so cheap, why are my electricity bills going up year on year well ahead of inflation?

That day will come, and those that pushed this narrative will have to answer when the music stops.

And why do the countries with the most wind and solar have the highest energy prices? and of course energy prices as the biggest issue to economic competitiveness, no wonder growth has slowed to a standstill.