Mission Impossible: Growth and Net Zero

Labour’s two missions of economic growth and achieving a net zero grid by 2030 are mutually exclusive

Introduction

A new book is being launched by Lord Jon Moynihan about how Britain can return to growth. This is timely because the new Labour Government has set itself five missions to rebuild Britain. The first mission is to kickstart economic growth. They want to achieve the highest sustained growth in the G7 with “good jobs and productivity growth in every part of the country”. The Prime Minister emphasised growth as the number one objective in his speech in the Rose Garden. Mission number two is to Make Britain a clean energy superpower” to “cut bills, create jobs and deliver security with cheaper zero-carbon electricity by 2030, accelerating to net zero.”

There is much to commend in Moynihan’s book. In an article promoting it, he calls for less Government spending, lower taxes and rolling back stifling regulations. These are all necessary to get back to growth. However, one thing missing from his analysis is the role high energy prices play in stifling productivity growth, leading to economic stagnation.

This article will show that their top two missions are mutually exclusive. They cannot achieve top-tier growth and a net zero grid simultaneously, partly because they are misguided by claiming zero-carbon renewables are cheaper. Achieving one will destroy the chances of meeting the other.

UK Productivity Lagging

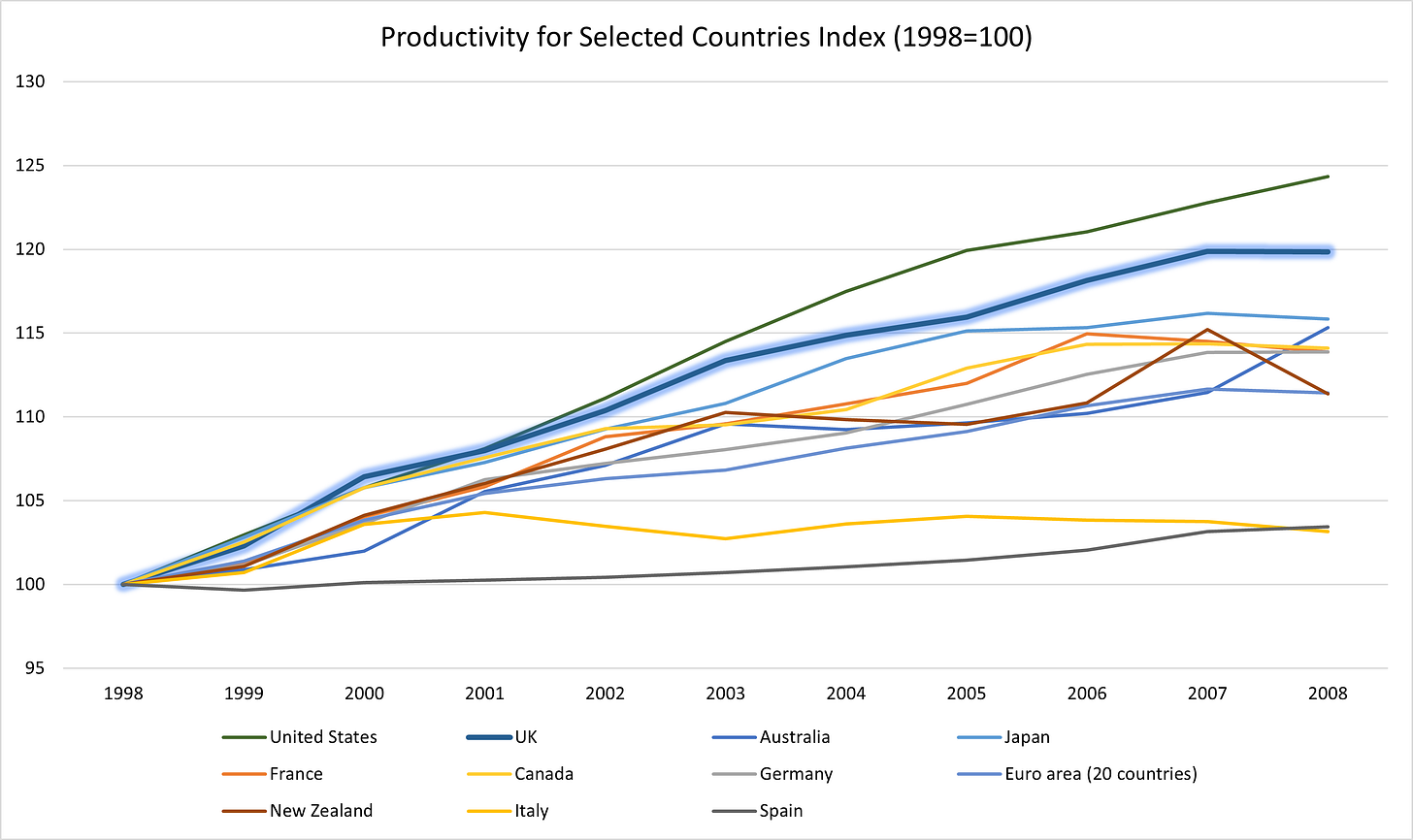

The new Government rightly assert that the key to long term sustainable growth is through improvements in productivity. In the period 1997-2008, the UK was a leader in productivity growth, as shown in Figure 1 (data from OECD).

However, since 2008 the situation has deteriorated and the UK is now a productivity laggard as seen in Figure 2.

To find out why this might be, we need to dig deeper into productivity statistics.

UK Productive Industries Shrinking

Helpfully, the ONS produces comprehensive data on the gross value added (GVA), hours worked and productivity of the UK economy by industry sector. Productivity is measured as the GVA per hour worked.

The economy is broken down into major industries and further sub-divided into sectors. Starting with major industries, it is helpful to look at how the GVA share of the economy has changed over time as shown in Figure 3.

The lines on the chart are expressed as an index, with the share of the whole economy indexed to 100 in 1997. At the top level, Services have grown faster than the economy as a whole. They grew from a 69.2% share in 1997 to 78.6% in 2023. Construction grew from 5.5% to 7.3% in 2007. It then suffered during the financial crisis, falling to 5.9% in 2012 before recovering to 6.9% in 2023. Productive Industries fell from 25.3% of the economy in 1997 to 14.5% in 2023. The economy has made a transition away from productive industries towards services. The trouble is, with some notable exceptions, services and construction have lower productivity than productive industries as we shall see below.

UK Productivity versus Growth by Sector

By drilling into the sector level data, we can compare the relative growth rates to the productivity of each sector and the result is shown in Figure 4.

It is worth dwelling on this chart. The x-axis shows the relative growth compared to the whole economy from 2008-2023, where 100% is the growth in the whole economy. The y-axis is an index of productivity of each sector in GVA per hour, where 100% is the whole economy.

The chart has been divided into quadrants. The green quadrant contains High-Growth/High-Productivity sectors such as Financial Services, Real Estate and Information & Communications. Financial Services is 270% more productive than the whole economy and has grown 118% faster than the rest of the economy. Clearly, we should be doing all we can to encourage these sectors to flourish.

The yellow quadrant is High-Growth/Low-Productivity sectors which includes Services as a whole, as well as sectors such as Arts and Entertainment, Health & Care and Professional, Science & Technology. It might be argued that with an aging population, then health is bound to be growing compared to the whole economy. However, we should be asking questions about how we can improve the productivity of all those sectors in the yellow quadrant. Interestingly, the Professional, Scientific & Technical sector includes lawyers, accountants, management consultants and environmental consultants. This sector has grown at 153% of the whole economy yet is only 95% as productive. Perhaps we should ask the consultants to heal themselves.

The white quadrant contains Low-Growth/Low-Productivity sectors including Construction, Education, Wholesale & Retail.

The red quadrant that shows Low-Growth/High-Productivity sectors is the most worrying. Mining and Extraction (which includes oil and gas) is the most productive sector in the whole economy. It has not only shrunk relative to the whole economy, but it has also shrunk in absolute terms from £29.4bn GVA in 2008 to £14.2bn in 2023. It remains the most productive sector despite GVA per hour falling by about half since 2008. A similar story emerges for all manufacturing and productive industries; they are more productive than the rest of the economy, but their share of the economy has shrunk since 2008. The GVA per hour for electricity and gas supply is probably skewed by high energy prices, because as we saw in an earlier article, productivity of electricity generation has been falling in terms of TWh per hour worked. If we are to boost productivity and economic growth, the productive industries in the red quadrant need to grow faster than the rest of the economy.

In summary, low productivity sectors are growing faster than the economy as a whole and many high productivity sectors are growing more slowly, with some even outright shrinking. It should come as no surprise that overall productivity is lagging that of other countries.

Role of Energy Costs

Energy is required to make things. Expensive energy makes it more expensive to make stuff. We can get an explanation of why productive industries are lagging by looking at energy costs. As shown in Figure 5, according to Government Data (Table 5.4.1), the UK had the most expensive industrial electricity prices in Europe in the latter half of 2023.

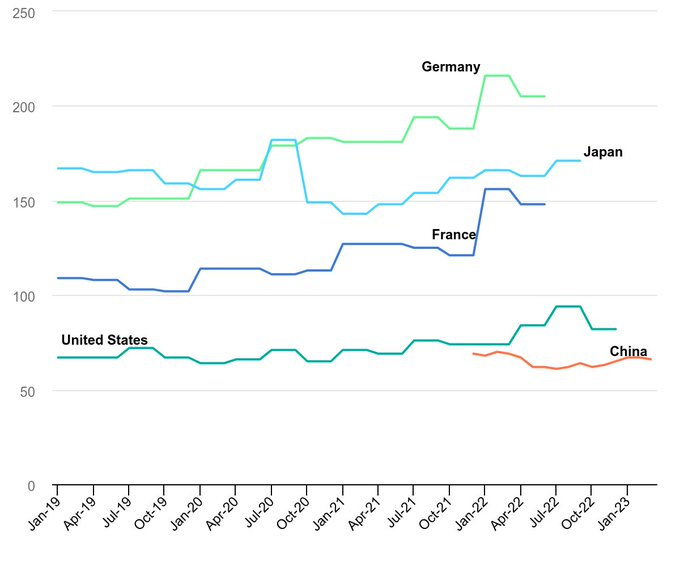

Moreover, according to the IEA, which sadly does not include the UK in its chart, German industrial electricity prices were 2-3 times more expensive than the US and China in mid-2022, see Figure 6. This probably means UK industrial electricity prices are even more expensive than the US and China.

There is a similar story with gas prices. At the time of writing, UK and EU gas prices are five times more expensive than gas at the Henry Hub in the US. It is clear the reason the UK and much of the EU is deindustrialising is because of high energy costs. It is simply much cheaper to make things abroad. Of course, making things abroad probably makes global CO2 emissions worse than if we made them at home.

Labour Policies for Growth and Net Zero

Labour’s plans for growth include planning reform to build 1.5m new homes and creating a National Wealth Fund to “invest in jobs.” It is obvious that we need to build more houses, but construction is less productive than the whole economy, so boosting construction is not going to achieve their objective of growing overall productivity. They are going to borrow to create the National Wealth Fund and use the money to spend on technologies such as green hydrogen and carbon capture and storage, both of which will make energy more expensive.

Labour has also awarded large pay rises to teachers, train drivers and NHS doctors without demanding any improvements to working practices or productivity. With more pay for no increase in output, the already weak productivity in Transport, Health and Education is bound to deteriorate further.

Labour also wants to increase the windfall tax on oil and gas and remove investment allowances. It has been reported that these changes will sound a “death knell” for the North Sea oil and gas industry. In effect, their tax policy is going to kill off our most productive industry.

We then come to Labour’s energy policy. They have announced plans that GB Energy will spend on floating offshore wind, tidal power and green hydrogen. In AR6, floating offshore wind was awarded contracts at ~£140/MWh in 2012 prices or £195/MWh in today’s money, which is about three times recent wholesale electricity prices. Tidal Stream power won contracts at £172/MWh in 2012 prices, or a staggering £240/MWh in 2024 prices. In December, the Government announced the results of its first green hydrogen auction. The average price offered was £175/MWh in 2012 prices which equates to £244/MWh in 2024 prices. Electricity made from this green hydrogen would cost over £500/MWh. These prices compare to market rates of ~£65/MWh in the first four months of this financial year. GB Energy is going to push up electricity prices to even greater heights.

Moreover, the awards for solar, onshore and offshore wind in AR6 at 2024 prices are also higher than current market rates as shown in Figure 7.

Higher electricity costs will lead to further decline in our productive industries. Even worse, high energy costs function as a tax on the whole economy and will stifle growth in other sectors and leave consumers with less disposable income.

Conclusions

Labour’s policies are delivering the exact opposite of what is needed to achieve their primary mission. If Labour wants to boost productivity and economic growth they need low energy prices. If they continue down the path to Net Zero, higher energy costs are inevitable. It is mission impossible to achieve both growth and Net Zero at the same time.

If they really do want growth, they need to pursue a different path. This would be to abandon Net Zero, end subsidies for renewables, cut the windfall tax, licence new oil and gas and get fracking. Boosting the oil and gas sector will increase the supply of gas, bring down prices, improve productivity and create a platform for growing the whole economy.

Readers may wish to forward this article to their MP, especially if they have a Labour MP, and ask them to ask the Government how it is going to achieve the top two missions simultaneously. You can find out how to contact your MP on this link.

The podcast version of this article can be found on these links to Spotify, Apple and YouTube

If you enjoyed this article, please share it with your family, friends and colleagues and sign up to receive more content.

David. Can I add two key points to your discussion of productivity. Understandably, economists and others focus on labour productivity, because that is what translates immediately to potential income and consumption per head. But labour productivity isn't really an independently measured variable in any economy that is dominated by non-traded services. How do you know what the productivity of a hairdresser or social worker is? There is no independent measure of the value of their output, so what one finishes up with is a circular analysis - haircuts are worth what people pay for them; hairdressers charge a price that reflects what they want to earn; so productivity is largely measured by wages. Even more so with social workers.

1. By sacrificing productive sectors, we are committing ourselves to a future in which the dominant form of productivity growth depends on increasing the wages paid to service workers and, thus, the prices charged for those services. That is a vicious circle because fewer people can afford the higher prices, whether for tourist facilities or lawyers. The end result is an economy based on serving a rich elite who monopolise the high paid activities but with a largely impoverished workforce. Sound familiar - that is not only the US & UK today but ancien regime France, Germany, Russia. This does not end well!

2. In productive sectors, labour productivity is a function of capital accumulation and productivity. More output per head requires heavy investment. The energy transition leads to a drastic reduction in capital productivity through the economy - not just in energy production but in its use. That is what kills productive businesses. But this shift also diverts our limited capital funds from investments needed to increase productivity in the rest of the economy. You can't increase spending on transport or health care if all of the money has gone into wind farms or heat pumps or electric vehicles. That, on its own, is the clearest reason why accelerated economic growth and Net Zero are mutually incompatible.

But ... none of this will convince two overlapping groups:

(a) Those who believe that Net Zero is essential to save the world. There has never been a remedy for religious belief apart from painful disillusionment! Such beliefs are fact-free because they exist in an invented world completely divorced from what is going in the real world. What is worse is that such beliefs are true luxury beliefs, funded out of guilt by those who are benefitting from the increasing unbalanced distribution of income.

(b) Those who believe (genuinely) that technology has changed or will change everything and that the costs of low carbon technologies have fallen by several orders of magnitude. The mythology of the computer chip cannot be punctured, even though a modern smartphone is incredibly powerful not because of technology but largely because it costs 50 times (in real terms) what simple phones cost 30-40 years ago.

Last night I wrote to my MP saying that the proposals for net zero currently envisioned involve the UK using less energy in 2050 than in 2020. One of your previous articles pointed me towards that Government plan. I am confident that reduced energy use and economic growth are mutually exclusive. I asked my MP to advocate fir an agenda for abundance which would involve high energy use going forward. Thank you for your work. As I put together my message to my MP I was grateful for your work bringing this problem to society's attention. Thank you!