Introduction

COP28 got off to a shaky start when COP28 president, Sultan Al Jaber claimed there was “no science” indicating that phasing out fossil fuels is needed to limit global warming to 1.5oC. He also suggested that phasing out fossil fuels would take the world back into caves (see Figure 1).

Predictably, this statement of the bleeding obvious caused an outbreak mouth-frothing amongst the masses of climate activists who had flown to Dubai, many on private jets, to tell the rest of us to reduce our carbon footprints.

Throughout the conference, various activists could be seen demanding an end to fossil fuels as the example in Figure 2 demonstrates.

After all the fire and brimstone, the activists are now claiming victory as the text of what is called the “first global stocktake”, called for a transition away from fossil fuels.

This article explores some of the COP28 agreements, the chances of them being met and the impact on humanity if the activists get their way.

What was agreed at COP28?

It turns out that the agreement on fossil fuels was, despite the hype, quite weak. In COP-speak “calls on” is the weakest call-to-action verb, with “instructs” being the strongest. The call was to transition away from fossil fuels in energy systems (see Figure 3). It seems that using fossil fuels in the production of fertiliser is safe, for now. What is not clear is whether “energy systems” includes transport which is of course a system that uses lots of energy.

The text also calls on nations to triple renewable energy capacity by 2030. At first, this sounds impressive, but will likely not lead to a tripling of renewable energy output. This is because the renewables category includes hydropower and biomass that can have high load factors. Wind and solar have low load factors and even if they more than triple capacity of these technologies, this will not lead to a tripling of overall renewables output.

One aspect of the declaration has been overlooked is that it also calls for spending on removal technologies such as carbon capture, utilisation and storage (CCUS) to accelerate. CCUS is effectively an energy tax on hydrocarbon-fired electricity generation that reduces power-plant efficiency. This means that to produce the same amount of electricity with CCUS will require even more coal or gas than without. So much for transitioning away from fossil fuels.

In addition, a group of nations, including the UK, took advantage of the COP28 forum to agree to triple nuclear capacity, even though this agreement did not form part of the formal COP28 negotiations.

Credibility of the COP28 Target to Triple Renewables

So, how likely is it that renewables capacity can be tripled by 2030? To find out, I analysed the history of renewables capacity from the International Renewables Energy Agency (IRENA) and projected the trends forward as can be seen in Figure 4.

Back in 2010 there was about 1,324GW of renewables installed capacity, with the vast bulk of it (1,025GW) being hydropower. By 2022, there was 3,518GW of installed capacity with 1,392GW of hydropower. Geothermal and bioenergy make up a relatively trivial part of the overall mix. The vast bulk of the increase in installed capacity has come from wind and solar, growing from a total of 223GW in 2010 to 1,960GW in 2022.

Now looking forwards, to meet the COP28 target of tripling renewables capacity, that would mean a total installed capacity of 10,553GW. If the other renewables categories expand at their current linear rate, wind and solar would have to expand by a factor of 4.25 between now and 2030 to 8,740GW. 262GW of new wind and solar capacity was added in the year to 2022. To meet the 2030 target, the rate of new additions would have to increase by a factor of 3.2 to 847GW per year, starting this year.

[Update 20 Dec 2023]: Figure 4 updated and the figures relating to the trendline updated to correct an error in the original trendline. The change increases the expected renewables capacity by 2030 slightly, but does not change the overall message.[/Update].

Looking at it another way, if we extend an exponential trend line of the renewables total installed capacity out to 2030, the capacity rises to about 6,600GW. The difference between the target and the trend is 3,953GW. That is what I will term the COP28 Renewables Target Credibility Gap.

I think we can file this under “Never Going to Happen”. It is all very well setting specific targets, but if the underlying reality does not match the ambition, then the target is not going to be met and is, in effect meaningless.

Will the UK Hit the COP28 Target to Triple Renewables by 2030

Of course, the UK has signed up to the target to triple renewables too, so it is helpful to look at whether the UK will hit the target to triple renewables by 2030. We are supposed be showing “climate leadership” after all. Figure 5 below shows the actual UK renewables capacity from 2009 to 2022 (sourced from Energy Trends Table 6.1).

Actual solar capacity (yellow line) in 2022 was 14.6GW, onshore wind (blue line) 14.8GW and offshore wind (green line) 13.8GW. Other renewables (purple line) comprising biomass (mostly burning trees at Drax), waste, hydro, landfill gas and other miscellaneous sources amounted to 10.2GW. Total capacity in 2022 was 53.5GW, so tripling capacity by 2030 means we need 161GW by then.

Extending the trend of installed capacity out to 2030 means we will have 27.6GW of solar, 24GW of onshore wind, 19.9GW of offshore wind and 14.6GW of other renewables. This gives a total of ~86GW, some 75GW short of the target. The individual targets for solar (yellow triangle), onshore (blue square) and offshore (green square) wind required to hit the overall goal of tripling renewables are even higher than the magical thinking in Ed Miliband’s plan. Assuming the other renewables get continue to expand at the current rate (purple square), there will be a shortfall of ~25GW of solar, ~12GW of onshore wind and ~38GW of offshore wind.

Remember that no offshore wind contracts were awarded in AR5 this year and the awards for solar and onshore wind were at nowhere near the rate required to hit the tripling target. I think it is safe to say that this is not going to happen either. It appears that the only place where the UK is leading is in the renewable energy fantasy league.

How Credible is the Pledge to Triple Nuclear Power?

Fortunately, there is better news when we look at the pledge to triple nuclear capacity by 2050. In this article, I examined the nuclear renaissance that is happening largely in Asia and India. The WNA has produced three scenarios for nuclear power out to 2040 as seen in Figure 6.

Their Reference Scenario predicts a near doubling of nuclear capacity from the 366GW in 2022 to 686GW in 2040. The Upper Scenario predicts a total of 931GW on the same timeframe. Provided we hit somewhere between the Reference and Upper Scenarios by 2040, it is realistic to expect to see nuclear capacity tripling from 2022 levels to 1,100GW by 2050.

It is ironic that the only target set during COP that looks achievable is the one set outside the formal COP28 process.

Credibility of COP28 Call to Transition from Fossil Fuels by 2050

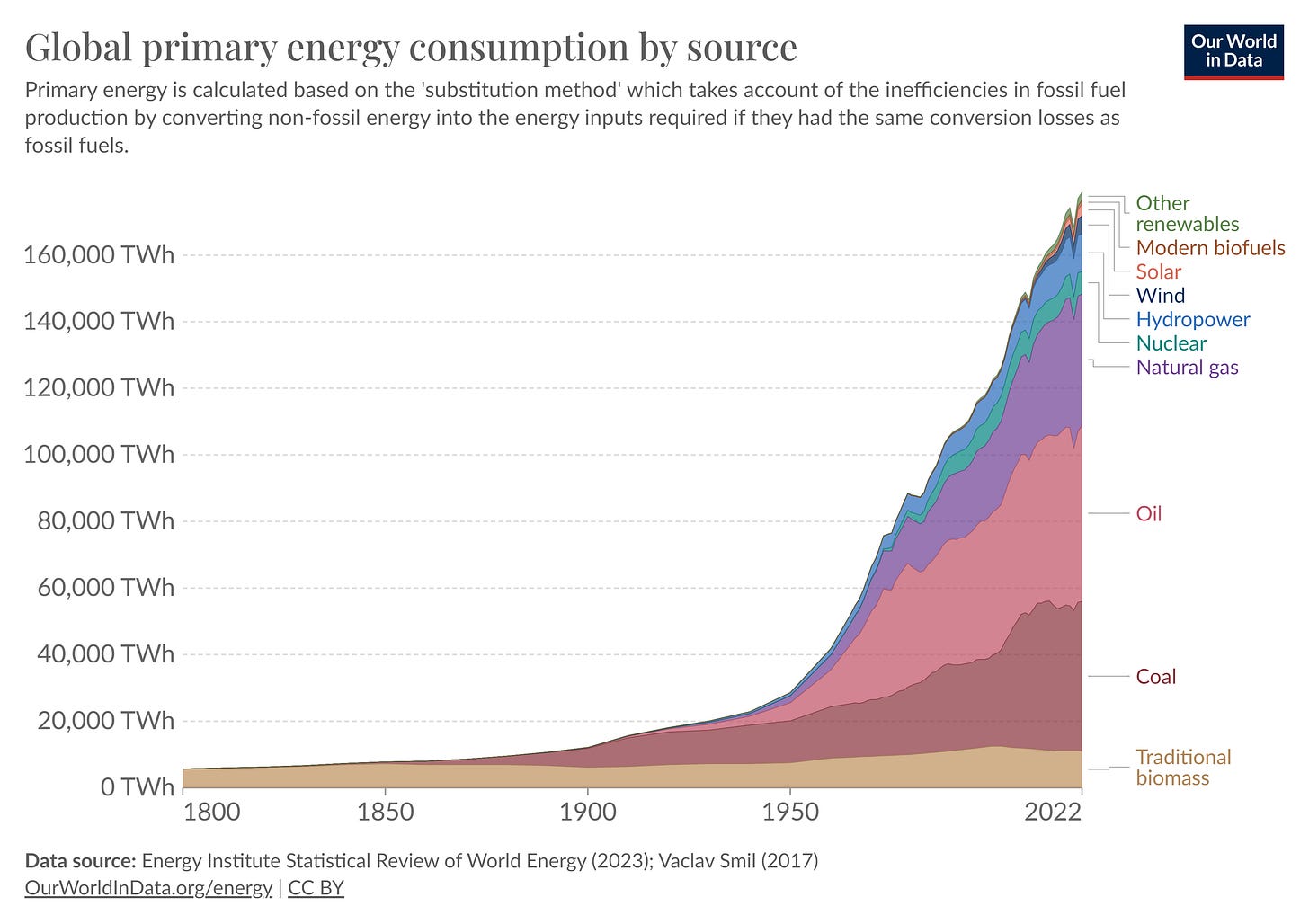

It is now time to look at what a transition away from fossil fuels might look like. The starting point here is Our World in Data’s global energy consumption by source as shown in Figure 7.

It is interesting how the first use of fossil fuels around 1850 and the big rise since around 1950 has coincided with the development of the modern world and the thriving of humanity. No wonder Kenyan farmer Jusper Machogu told COP28 that Africa needs fossil fuels to develop their economy and support human flourishing.

Note the chart above uses the “substitution method” for renewables to account for the inefficiencies in using fossil fuels. Broadly speaking, they multiply the actual generation from nuclear, wind and solar by a factor of ~2.6 because electricity from those sources is usable energy, whereas ~60% of the energy in fossil fuels is lost as waste heat when burned to generate electricity or to propel vehicles. In essence, the substitution method attempts to convert renewables into fossil fuel equivalent units. This is understandable up to a point, but soon they are going to have to account for round trip losses in making say, hydrogen, to make a renewables-only grid reliable. However, let us take this as read for now.

The other point to note is that this chart includes all energy, not just power generation, so transport and industrial heat is included. As mentioned above, the COP28 call is to transition away from fossil fuels for energy systems and it is not clear if transport demand is included. However, given the strong push towards using more electric vehicles (EVs) which will use power from the energy system of the grid, then I think it is appropriate to look at total energy.

Figure 8 uses the data from the chart above, zooming in on the period since 2010 and extrapolates out to 2050.

Using the substitution method described above, total energy consumption in 2022 was 178,899TWh, with the vast majority (77%) coming from fossil fuels. Wind and solar delivered about 5% of total energy. Despite a dip during 2020, consumption of fossil fuels has risen steadily since 2010. If we extend this total energy consumption out to 2050 using a linear trend, we might expect total energy consumption to rise to around 251,401TWh.

To understand how this might be delivered, we can use the pledge to triple nuclear power by 2050, growing from 6,702TWh in 2022 to 20,107TWh in 2050. If we take the renewables category as a whole and extend it out to 2050 using an exponential trend line, total renewables generation goes up from 34,960TWh in 2022 to 80,807TWh in 2050. In doing so, the extra renewable generation of 1,525TWh delivered in 2022 compared to 2021 goes up to 2,443TWh in 2050 compared to 2049. In other words, the annual rate of increase goes up by 60%. Given that traditional biomass consumption is steady, and hydro is very slow growing, this requires massive increases in solar and wind capacity, perhaps a five- or six-fold increase on 2022 levels. Even if the sites and minerals can be found to place and make these machines, such an increase is a very tall order to achieve. Even then, such a plan will only achieve the further enrichment of crony capitalists addicted to subsidies.

However, even with this ambitious assumption, we only get to 100,914TWh from nuclear and renewables by 2050. This leaves a gap of 150,487TWh to be filled, or 60% of the expected demand. This gap is bigger than last year’s fossil fuel consumption of 137,237TWh. If we have “transitioned away” from fossil fuels, where will this energy come from? Even if the commitment to tripling nuclear energy is doubled to a six-fold increase, it would barely make a dent in the energy gap. Let’s call this the COP28 Energy Credibility Gap.

Conclusion

Alarmists make lots of vague claims about the catastrophe that faces us if global temperatures increase more than 1.5oC over pre-industrial levels. Very few of them ever acknowledge the benefits humanity has reaped from fossil fuels. Even fewer even consider the implications for us if we move to an energy scarce world. It is hardly worth contemplating a world where we are short more than half the energy we need. An energy scarce world would have a massive negative impact on humanity. Al Jaber was right, phasing out fossil fuels would take us back to living in caves and result in starvation and death on a biblical scale. There must come a point where we realise that the supposed cure is worse than the alleged disease.

Clearly the declarations from COP28 are nothing more than elaborate performance art. It is time to end this charade of COP meetings before they do even more damage. Perhaps we should ask the delegates to make their way home on a pedalo, so they learn first-hand what they have in mind for us.

If you have enjoyed this article, please share it with your family, friends and colleagues and sign up to receive more content.

A problem that’s plagued climate negotiations since the enactment of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change in 1992 is the exemption of developing countries from any obligation (legal, moral or political) to reduce their emissions. That was initially made effective by Article 4.7 of the Convention and has continued ever since: it was confirmed by the Kyoto Protocol (COP3) in 1998, at the Copenhagen conference (COP15) in 2009 and, significantly, by The Paris Agreement (COP21) in 2015.

And, although few (if any) commentators seem to have noticed, it was confirmed last week at COP28.

It’s widely recognised that paragraph 28 of the ‘Dubai Agreement’ is its key provision – especially item (d) with its reference to ‘Transitioning away from fossil fuels’ – but few seem to have considered the impact of its opening paragraph. Yet that says that the Parties’ contribution must take ‘into account the Paris Agreement’. And that’s crucially important.

Here’s why: scroll down to paragraph 38. It ‘Recalls Article 4, paragraph 4, of the Paris Agreement, which provides that developed country Parties should continue taking the lead by undertaking economy-wide absolute emission reduction targets, and that developing country Parties should continue enhancing their mitigation efforts and are encouraged to move over time towards economy-wide emission reduction or limitation targets in the light of different national circumstances.’

Get that? Paragraph 28 says that parties must take account of the Paris Agreement. And the Paris Agreement – as specifically stated here in paragraph 38 – states that developing countries are merely ‘encouraged’ to move to emission cuts ‘over time’. And, so there’s no misunderstanding, paragraph 39 ‘Reaffirms Article 4.4’. In other words, as has been the case since 1992, developing countries are under no obligation to cut their emissions. Yet developing countries are the source of about 65% of global emissions.

The effect of the above is that only developed countries are affected by the transitioning provision (whatever it may mean) and, as some major developed countries (especially Russia) have no interest in complying, in practice it can apply only to Western economies. And they’re the source of barely 20% of global emissions. In other words, the Dubai Agreement is an absurd nonsense.

I can’t think of a single UK politician who questions the push to get rid of fossil fuels, despite the impossibility of this transition staring them in the face. Fossil fuels (mostly gas) only just kept the UK lights on over the early days of December when temperatures were below freezing and there was practically zero wind and solar. The current Gridwatch graph from mid-November to mid-December shows what a narrow squeak we had, yet these nutters blithely press ahead leading the country into an abyss: https://gridwatch.templar.co.uk/.